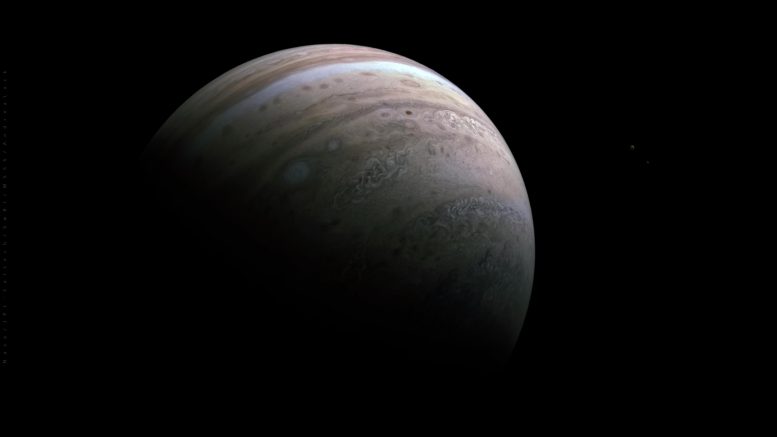

التقطت مهمة جونو التابعة لناسا هذا المنظر لنصف الكرة الجنوبي للمشتري في 12 يناير 2022 ، خلال مدار المركبة الفضائية 39. الائتمان: معالجة الصور بواسطة NASA / JPL-Caltech / SwRI / MSSS ، أندريا لاك

Jupiter’s southern hemisphere during the spacecraft’s 39th close flyby of the planet on January 12, 2022. Zooming in on the right portion of the image (see image below) reveals two more worlds in the same frame: Jupiter’s intriguing moons Io (left) and Europa (right).

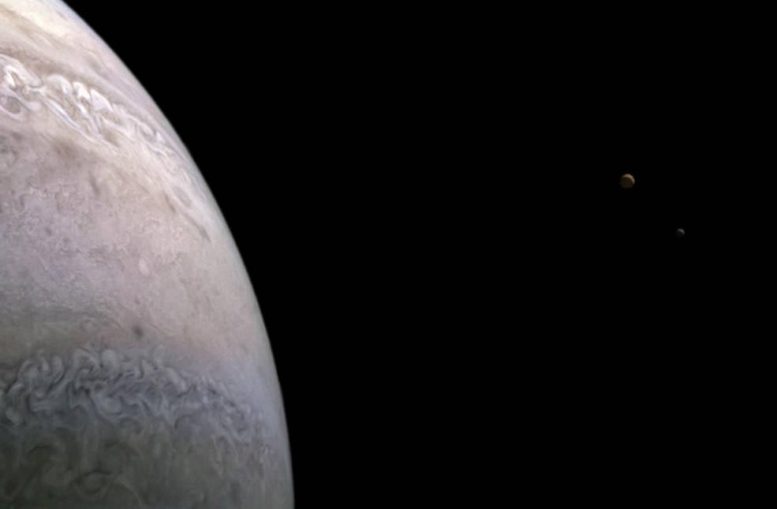

Zooming in on the right portion of the image at the top of the article reveals two more worlds in the same frame: Jupiter’s intriguing moons Io (left) and Europa (right). Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSS, Image processing by Andrea Luck

Io is the solar system’s most volcanic body, while Europa’s icy surface hides a global ocean of liquid water beneath. Juno will have an opportunity to capture much more detailed observations of Europa – using several scientific instruments – in September 2022, when the spacecraft makes the closest fly-by of the enigmatic moon in decades. The mission will also make close approaches to Io in late 2023 and early 2024.

At the time this image was taken, the Juno spacecraft was about 38,000 miles (61,000 kilometers) from Jupiter’s cloud tops, at a latitude of about 52 degrees south. Citizen scientist Andrea Luck created the image using raw data from the JunoCam instrument.

Juno captured another stunning image not too long ago — this time of Jupiter’s moon Ganymede, the largest and most massive moon in the Solar System.

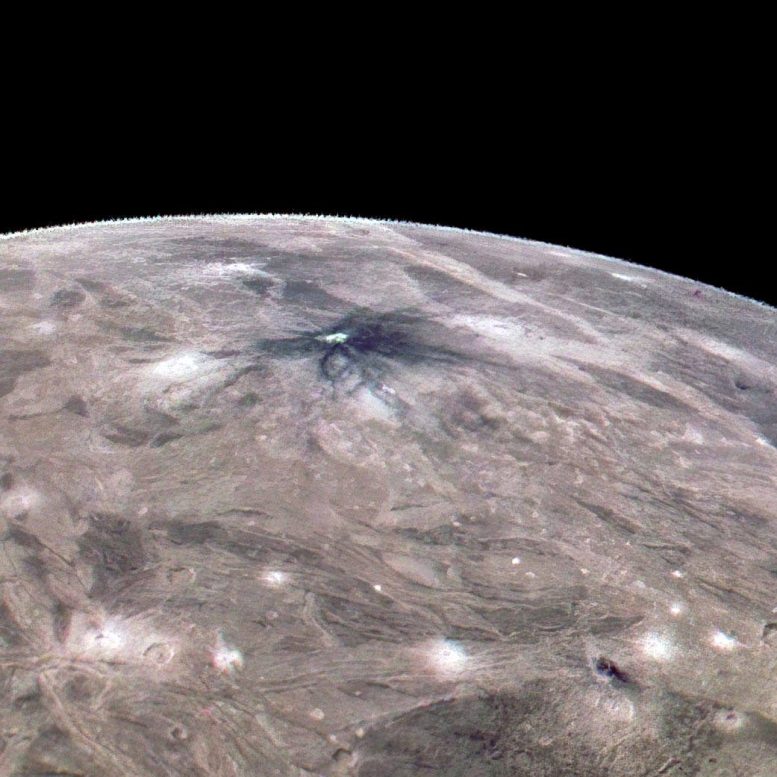

NASA’s Juno mission captured this look at the complex surface of Jupiter’s moon Ganymede during a close pass by the giant moon in June 2021. At closest approach, the spacecraft came within just 650 miles (1,046 kilometers) of Ganymede’s surface. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSS, Image processing by Thomas Thomopoulos

A Striking Crater on Jupiter’s Moon Ganymede

This look at the complex surface of Jupiter’s moon Ganymede came from NASA’s Juno mission during a close pass by the giant moon in June 2021. At closest approach, the spacecraft came within just 650 miles (1,046 kilometers) of Ganymede’s surface.

Most of Ganymede’s craters have bright rays extending from the impact scar, but about 1 percent of the craters have dark rays. This image taken by JunoCam during the close Ganymede pass shows one of the dark-rayed craters. The crater, named Kittu, is about 9 miles (15 kilometers) across, surrounded by darker material ejected during the impact that formed the crater. Scientists believe that contamination from the impactor produced the dark rays. As time passes, the rays stay dark because they are a bit warmer than the surroundings, so ice is driven off to condense on nearby colder, brighter terrain.

Ganymede is the largest moon in our solar system, larger even than the planet Mercury. It’s the only moon known to have its own magnetic field, which causes auroras that circle the moon’s poles. Evidence also indicates Ganymede may hide a liquid water ocean beneath its icy surface.

Citizen scientist Thomas Thomopoulos created this enhanced-color image using data from the JunoCam camera. The original image was taken on June 7, 2021.

“متعصب التلفزيون. مدمن الويب. مبشر السفر. رجل أعمال متمني. مستكشف هواة. كاتب.”

More Stories

خريطة جديدة للمريخ تكشف عن “هياكل” مخفية تحت سطح المريخ

زوج من نفاثات البلازما الضخمة تندلع من ثقب أسود هائل | الثقوب السوداء

الأسمنت المستوحى من عظام الإنسان أصعب بخمس مرات من الخرسانة العادية